A

Figure 3.

Case 3. A 13-year-old female with Ewing’s sarcoma. (A) PET image from PET/MR exam; (B) T2 frFSE Flex FatSat from PET/MR exam; and initial diagnostic MR exam (C) T2 frFSE Flex FatSat and (D) T1 contrast enhanced. The quality of the (B) T2 frFSE Flex FatSat on PET/MR is the same quality as the (C) T2 frFSE Flex FatSat on the dedicated MR.

B

Figure 3.

Case 3. A 13-year-old female with Ewing’s sarcoma. (A) PET image from PET/MR exam; (B) T2 frFSE Flex FatSat from PET/MR exam; and initial diagnostic MR exam (C) T2 frFSE Flex FatSat and (D) T1 contrast enhanced. The quality of the (B) T2 frFSE Flex FatSat on PET/MR is the same quality as the (C) T2 frFSE Flex FatSat on the dedicated MR.

C

Figure 3.

Case 3. A 13-year-old female with Ewing’s sarcoma. (A) PET image from PET/MR exam; (B) T2 frFSE Flex FatSat from PET/MR exam; and initial diagnostic MR exam (C) T2 frFSE Flex FatSat and (D) T1 contrast enhanced. The quality of the (B) T2 frFSE Flex FatSat on PET/MR is the same quality as the (C) T2 frFSE Flex FatSat on the dedicated MR.

D

Figure 3.

Case 3. A 13-year-old female with Ewing’s sarcoma. (A) PET image from PET/MR exam; (B) T2 frFSE Flex FatSat from PET/MR exam; and initial diagnostic MR exam (C) T2 frFSE Flex FatSat and (D) T1 contrast enhanced. The quality of the (B) T2 frFSE Flex FatSat on PET/MR is the same quality as the (C) T2 frFSE Flex FatSat on the dedicated MR.

A

3/30/18

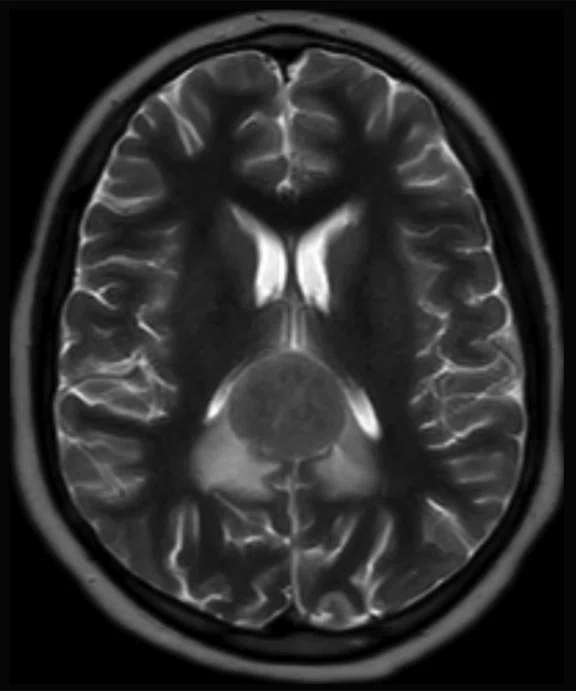

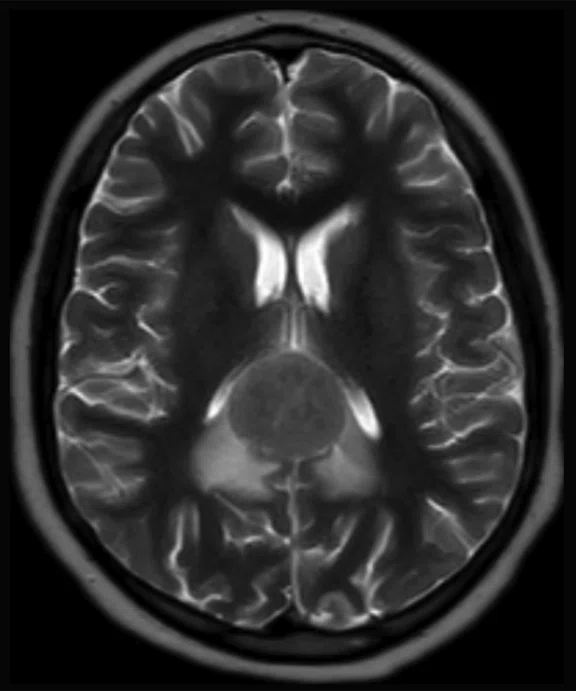

Figure 5.

Case 4. A 16-year-old with large B cell lymphoma, who relapsed with lesions in the brain. MR images acquired with PET/MR.

B

4/23/18

Figure 5.

Case 4. A 16-year-old with large B cell lymphoma, who relapsed with lesions in the brain. MR images acquired with PET/MR.

C

5/15/18

Figure 5.

Case 4. A 16-year-old with large B cell lymphoma, who relapsed with lesions in the brain. MR images acquired with PET/MR.

D

6/19/18

Figure 5.

Case 4. A 16-year-old with large B cell lymphoma, who relapsed with lesions in the brain. MR images acquired with PET/MR.

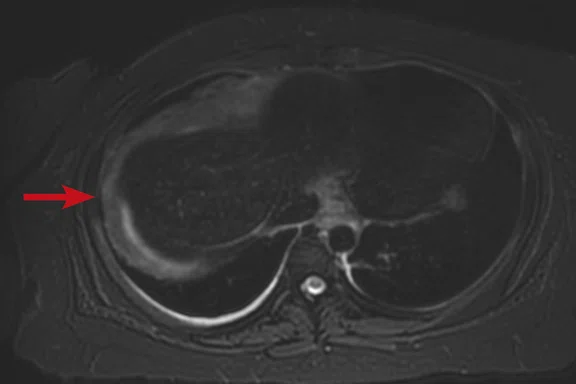

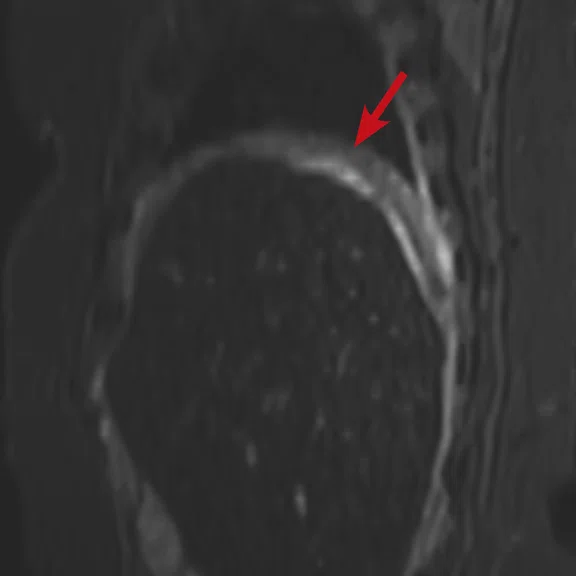

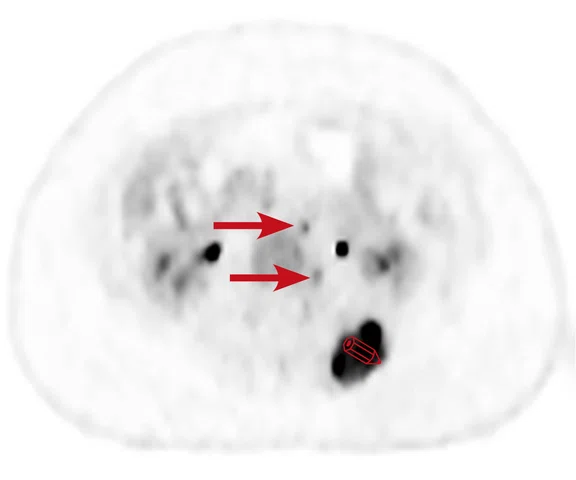

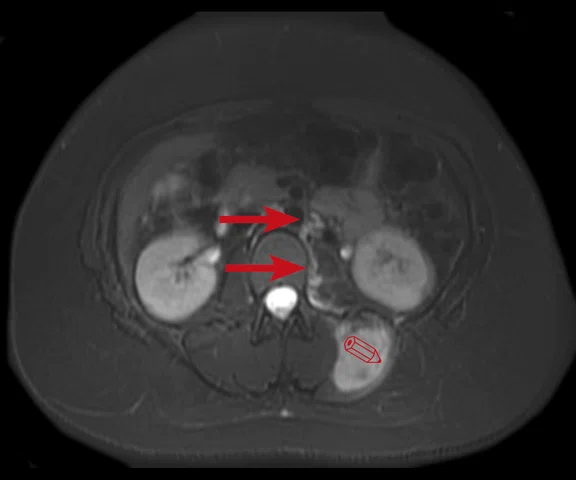

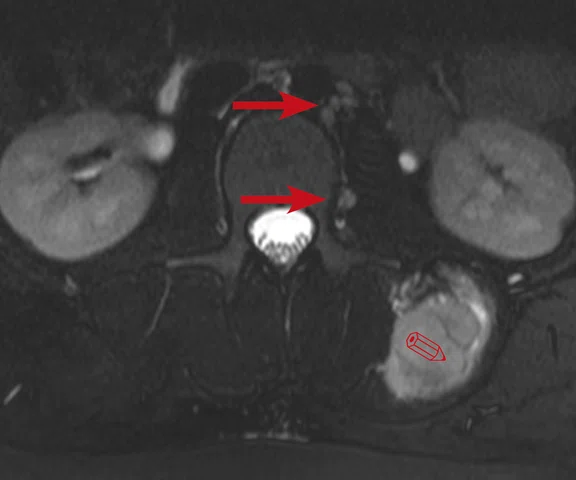

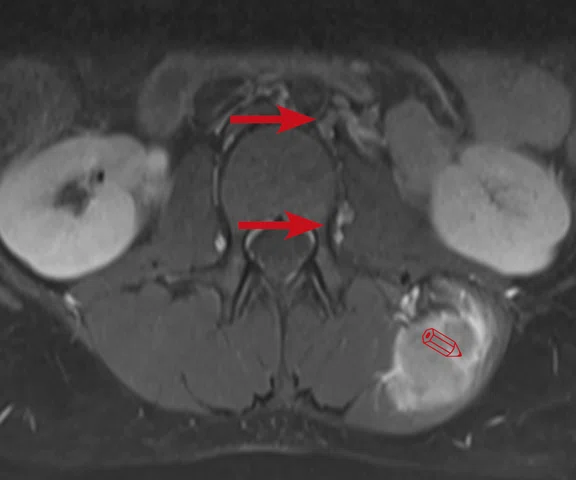

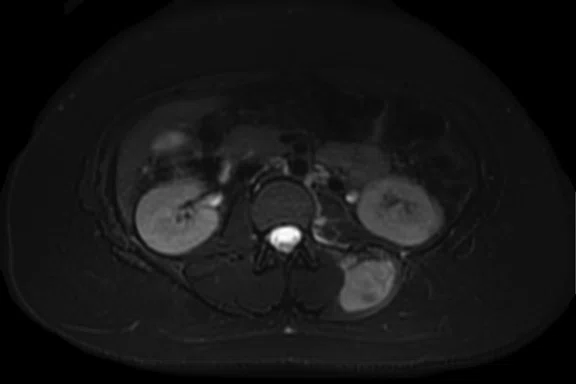

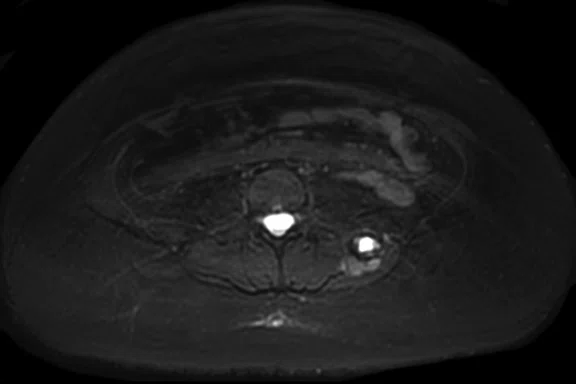

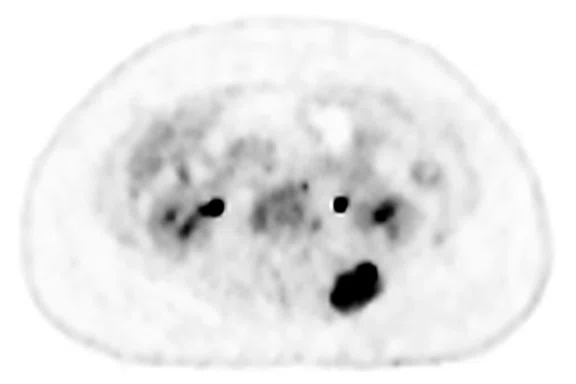

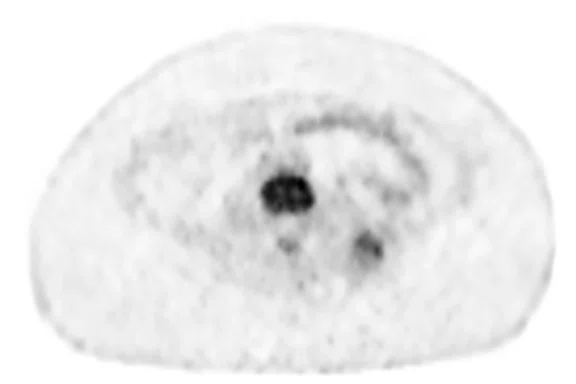

A

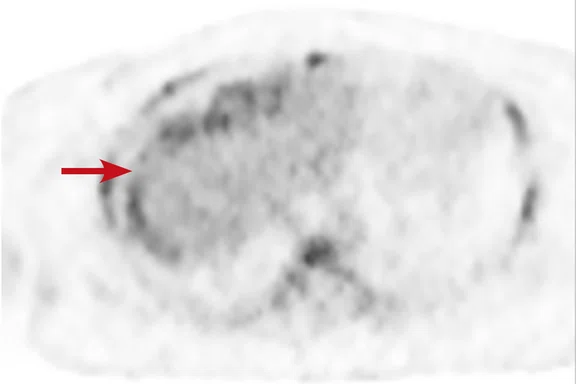

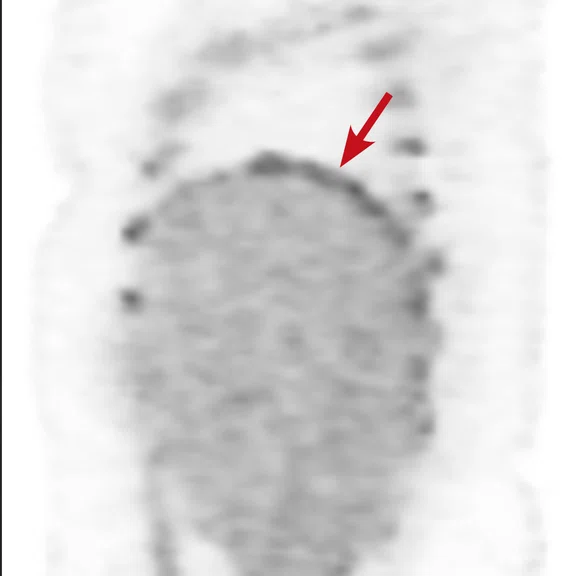

Figure 2.

Case 2. A 16-year-old patient with residual disease over the pleural surface of the diaphragm (red arrows). Despite imaging the patient two hours after FDG, good diagnostic quality images were still acquired on PET. The hyperdense residual lesion is well characterized by MR. (A, B) PET with (C, D) corresponding T2 FatSat MR slices.

B

Figure 2.

Case 2. A 16-year-old patient with residual disease over the pleural surface of the diaphragm (red arrows). Despite imaging the patient two hours after FDG, good diagnostic quality images were still acquired on PET. The hyperdense residual lesion is well characterized by MR. (A, B) PET with (C, D) corresponding T2 FatSat MR slices.

C

Figure 2.

Case 2. A 16-year-old patient with residual disease over the pleural surface of the diaphragm (red arrows). Despite imaging the patient two hours after FDG, good diagnostic quality images were still acquired on PET. The hyperdense residual lesion is well characterized by MR. (A, B) PET with (C, D) corresponding T2 FatSat MR slices.

D

Figure 2.

Case 2. A 16-year-old patient with residual disease over the pleural surface of the diaphragm (red arrows). Despite imaging the patient two hours after FDG, good diagnostic quality images were still acquired on PET. The hyperdense residual lesion is well characterized by MR. (A, B) PET with (C, D) corresponding T2 FatSat MR slices.

A

Figure 1.

Case 1. A 21-year-old patient with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, restaged with PET/MR. (A-C) Initial staging PET/CT; (D-F) Interim PET/MR; and (G-I) restaging PET/MR.

B

Figure 1.

Case 1. A 21-year-old patient with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, restaged with PET/MR. (A-C) Initial staging PET/CT; (D-F) Interim PET/MR; and (G-I) restaging PET/MR.

D

Figure 1.

Case 1. A 21-year-old patient with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, restaged with PET/MR. (A-C) Initial staging PET/CT; (D-F) Interim PET/MR; and (G-I) restaging PET/MR.

D

Figure 1.

Case 1. A 21-year-old patient with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, restaged with PET/MR. (A-C) Initial staging PET/CT; (D-F) Interim PET/MR; and (G-I) restaging PET/MR.

E

Figure 1.

Case 1. A 21-year-old patient with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, restaged with PET/MR. (A-C) Initial staging PET/CT; (D-F) Interim PET/MR; and (G-I) restaging PET/MR.

F

Figure 1.

Case 1. A 21-year-old patient with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, restaged with PET/MR. (A-C) Initial staging PET/CT; (D-F) Interim PET/MR; and (G-I) restaging PET/MR.

G

Figure 1.

Case 1. A 21-year-old patient with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, restaged with PET/MR. (A-C) Initial staging PET/CT; (D-F) Interim PET/MR; and (G-I) restaging PET/MR.

H

Figure 1.

Case 1. A 21-year-old patient with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, restaged with PET/MR. (A-C) Initial staging PET/CT; (D-F) Interim PET/MR; and (G-I) restaging PET/MR.

I

Figure 1.

Case 1. A 21-year-old patient with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, restaged with PET/MR. (A-C) Initial staging PET/CT; (D-F) Interim PET/MR; and (G-I) restaging PET/MR.

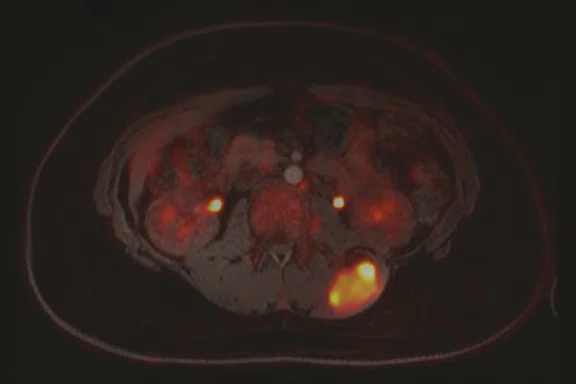

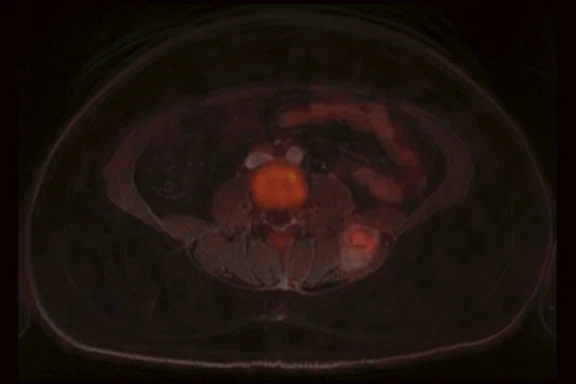

A

Figure 4.

Case 3. Adjuvant therapy shrunk the primary tumor and two hot spots leading to negative surgical margins. (A, C, E) PET/MR exam prior to treatment and (B, D, F) PET/MR two- and one-half months after start of treatment.

B

Figure 4.

Case 3. Adjuvant therapy shrunk the primary tumor and two hot spots leading to negative surgical margins. (A, C, E) PET/MR exam prior to treatment and (B, D, F) PET/MR two- and one-half months after start of treatment.

C

Figure 4.

Case 3. Adjuvant therapy shrunk the primary tumor and two hot spots leading to negative surgical margins. (A, C, E) PET/MR exam prior to treatment and (B, D, F) PET/MR two- and one-half months after start of treatment.

D

Figure 4.

Case 3. Adjuvant therapy shrunk the primary tumor and two hot spots leading to negative surgical margins. (A, C, E) PET/MR exam prior to treatment and (B, D, F) PET/MR two- and one-half months after start of treatment.

E

Figure 4.

Case 3. Adjuvant therapy shrunk the primary tumor and two hot spots leading to negative surgical margins. (A, C, E) PET/MR exam prior to treatment and (B, D, F) PET/MR two- and one-half months after start of treatment.

F

Figure 4.

Case 3. Adjuvant therapy shrunk the primary tumor and two hot spots leading to negative surgical margins. (A, C, E) PET/MR exam prior to treatment and (B, D, F) PET/MR two- and one-half months after start of treatment.

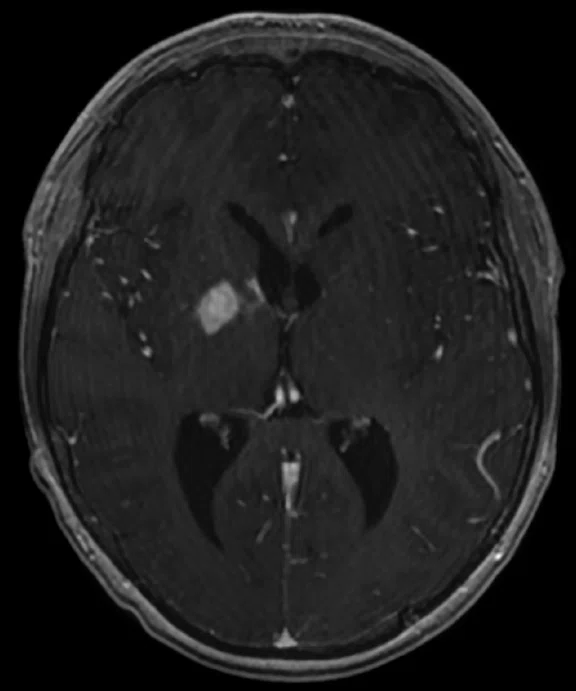

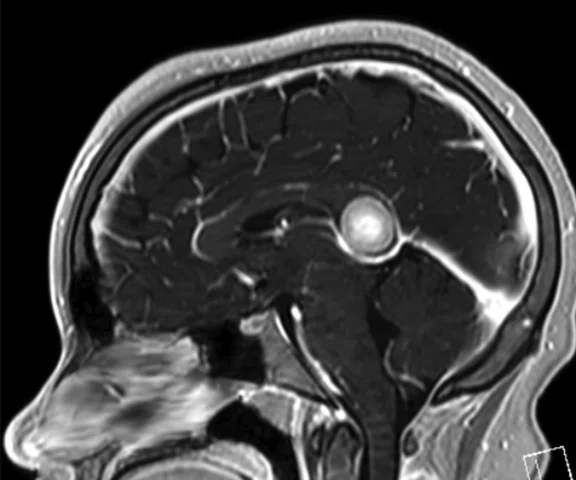

A

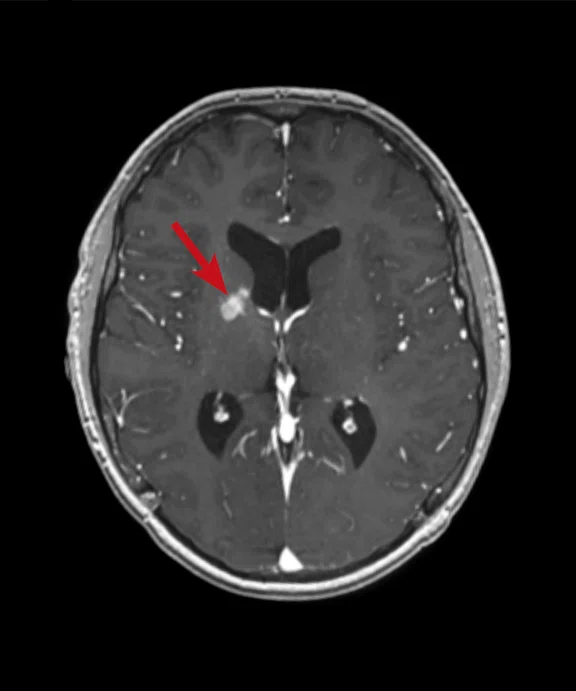

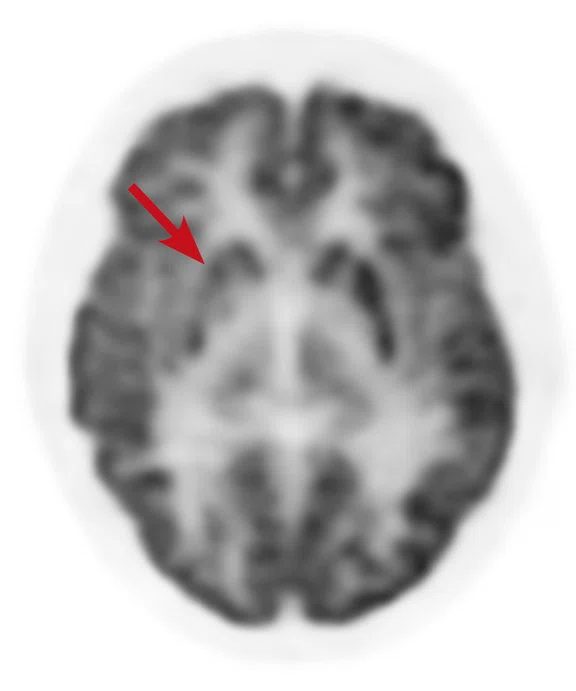

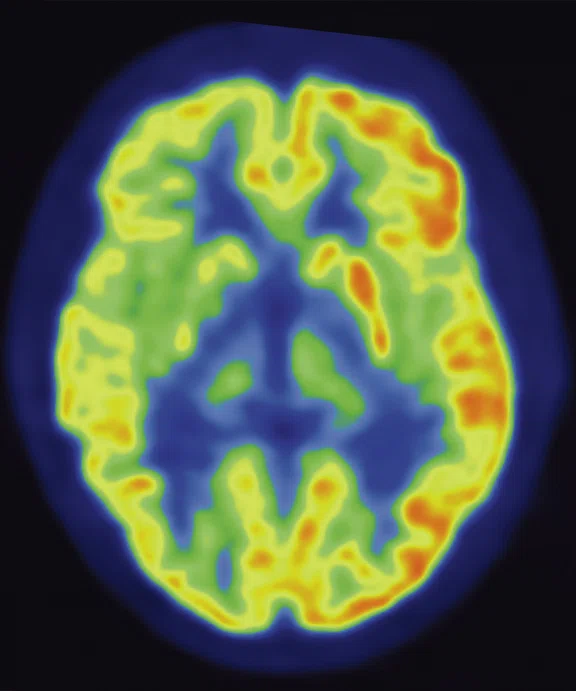

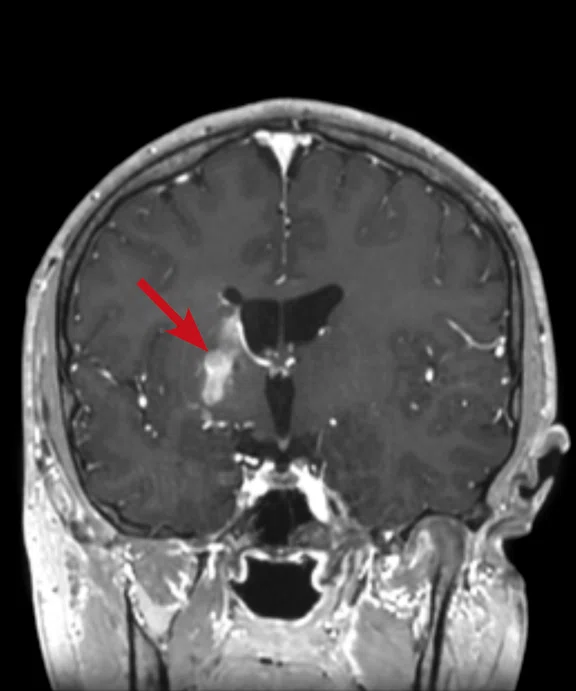

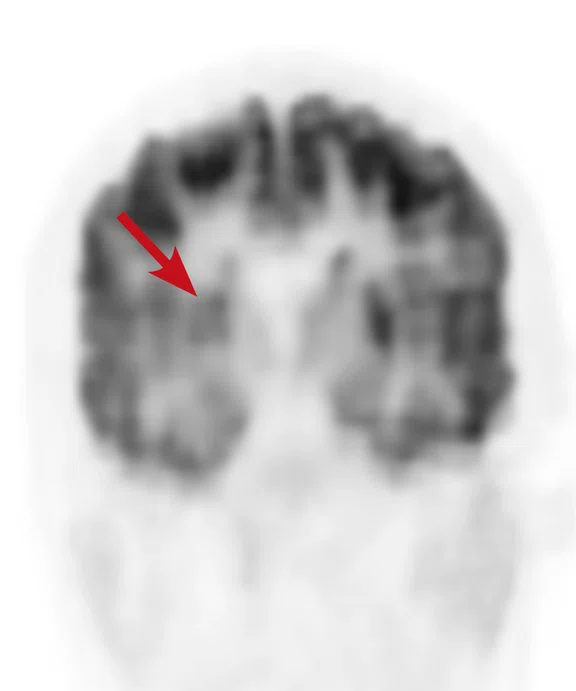

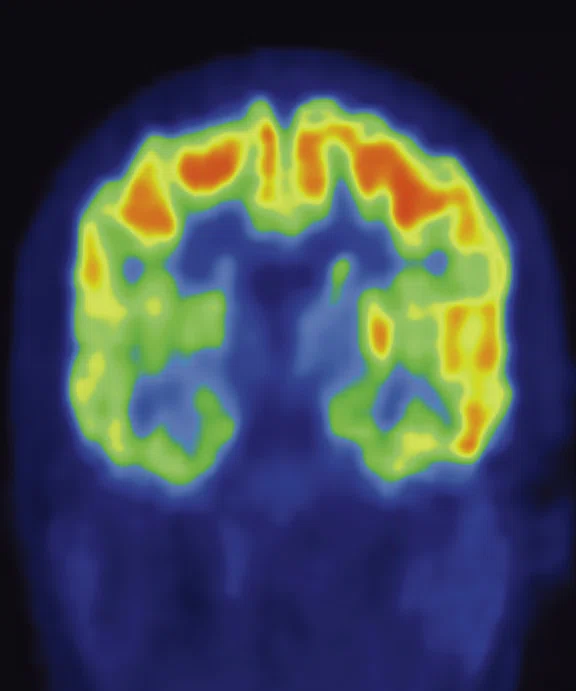

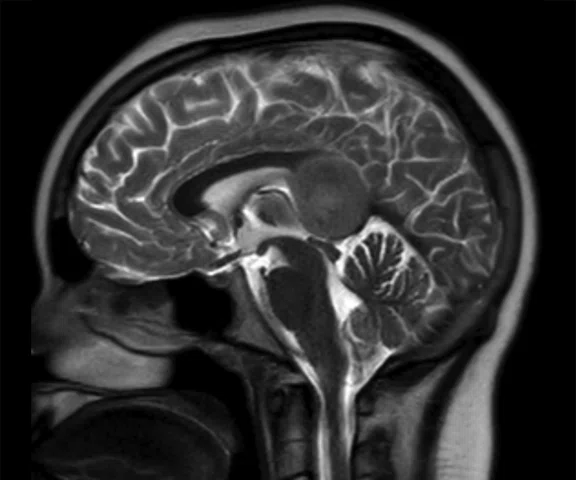

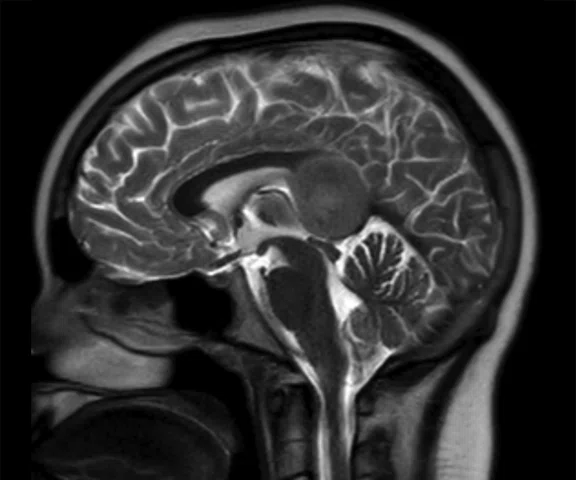

Figure 6.

Case 4. Same patient. Uptake in the right basal ganglia (B, E, red arrows) corresponds with enhancement on the MR (A, D, red arrows), suggestive of a residual lesion. (A, D) MR; (B, E) PET; and (C, F) fused PET/MR.

B

Figure 6.

Case 4. Same patient. Uptake in the right basal ganglia (B, E, red arrows) corresponds with enhancement on the MR (A, D, red arrows), suggestive of a residual lesion. (A, D) MR; (B, E) PET; and (C, F) fused PET/MR.

C

Figure 6.

Case 4. Same patient. Uptake in the right basal ganglia (B, E, red arrows) corresponds with enhancement on the MR (A, D, red arrows), suggestive of a residual lesion. (A, D) MR; (B, E) PET; and (C, F) fused PET/MR.

D

Figure 6.

Case 4. Same patient. Uptake in the right basal ganglia (B, E, red arrows) corresponds with enhancement on the MR (A, D, red arrows), suggestive of a residual lesion. (A, D) MR; (B, E) PET; and (C, F) fused PET/MR.

E

Figure 6.

Case 4. Same patient. Uptake in the right basal ganglia (B, E, red arrows) corresponds with enhancement on the MR (A, D, red arrows), suggestive of a residual lesion. (A, D) MR; (B, E) PET; and (C, F) fused PET/MR.

F

Figure 6.

Case 4. Same patient. Uptake in the right basal ganglia (B, E, red arrows) corresponds with enhancement on the MR (A, D, red arrows), suggestive of a residual lesion. (A, D) MR; (B, E) PET; and (C, F) fused PET/MR.

A

Figure 7.

Case 5. Initial PET/MR exam. A 12-year-old with undifferentiated sarcoma and widespread disease. (A, B) PET; (C, D) MR; and (E, F) fused PET/MR.

C

Figure 7.

Case 5. Initial PET/MR exam. A 12-year-old with undifferentiated sarcoma and widespread disease. (A, B) PET; (C, D) MR; and (E, F) fused PET/MR.

C

Figure 7.

Case 5. Initial PET/MR exam. A 12-year-old with undifferentiated sarcoma and widespread disease. (A, B) PET; (C, D) MR; and (E, F) fused PET/MR.

D

Figure 7.

Case 5. Initial PET/MR exam. A 12-year-old with undifferentiated sarcoma and widespread disease. (A, B) PET; (C, D) MR; and (E, F) fused PET/MR.

E

Figure 7.

Case 5. Initial PET/MR exam. A 12-year-old with undifferentiated sarcoma and widespread disease. (A, B) PET; (C, D) MR; and (E, F) fused PET/MR.

F

Figure 7.

Case 5. Initial PET/MR exam. A 12-year-old with undifferentiated sarcoma and widespread disease. (A, B) PET; (C, D) MR; and (E, F) fused PET/MR.

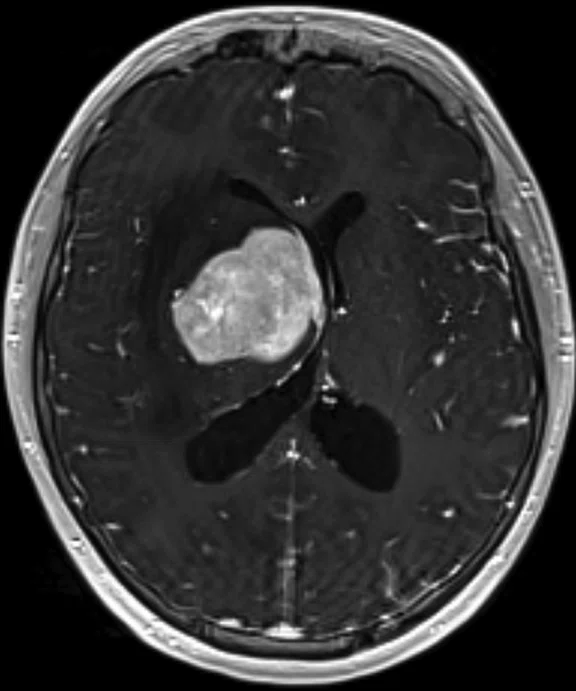

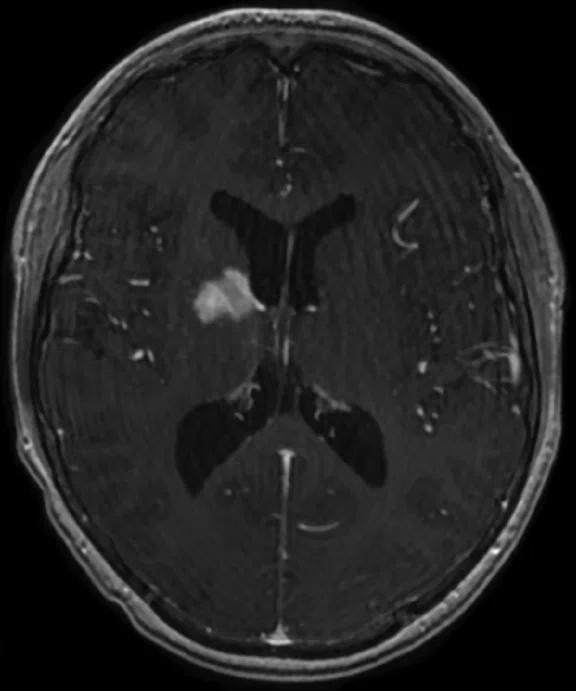

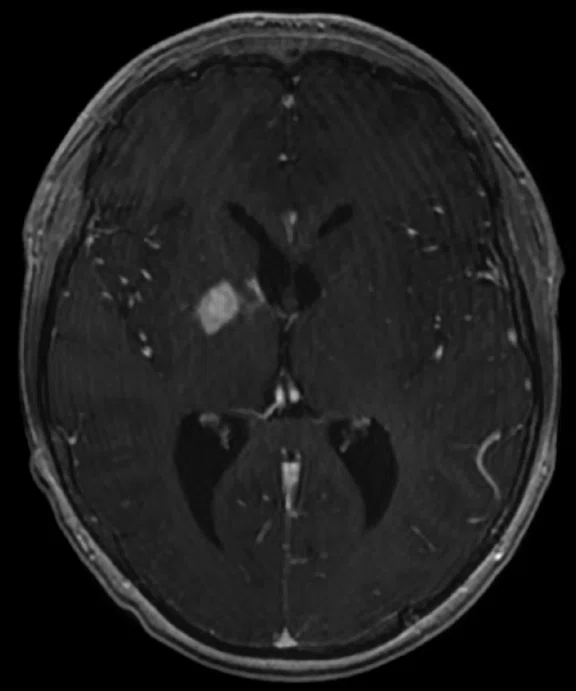

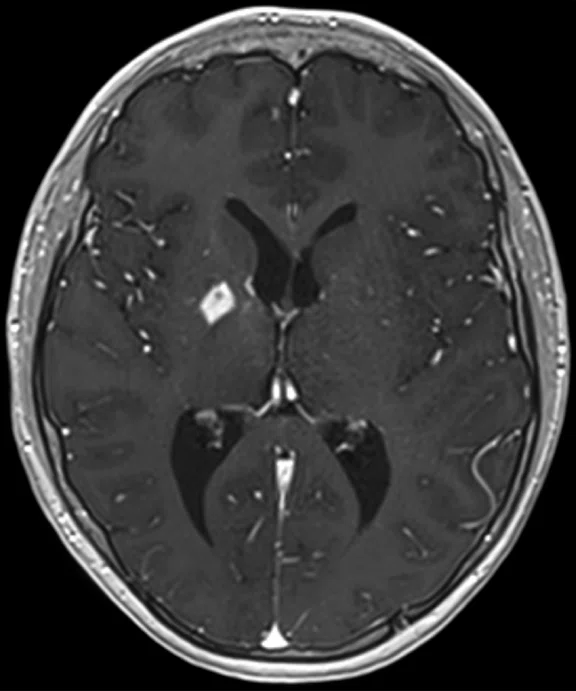

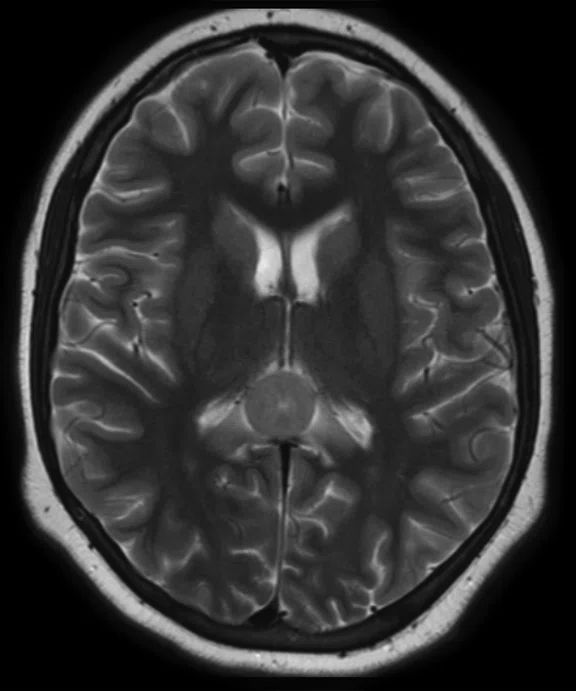

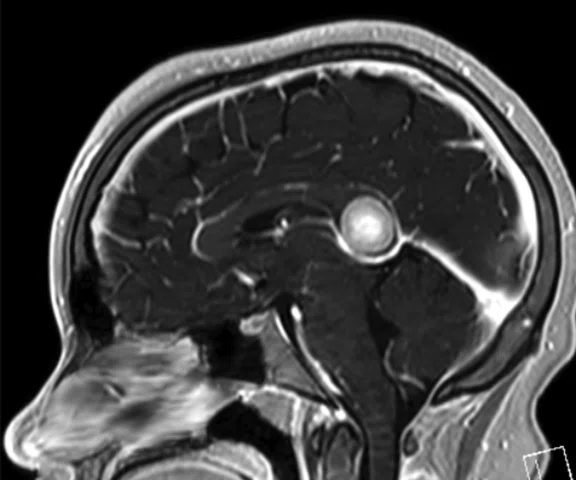

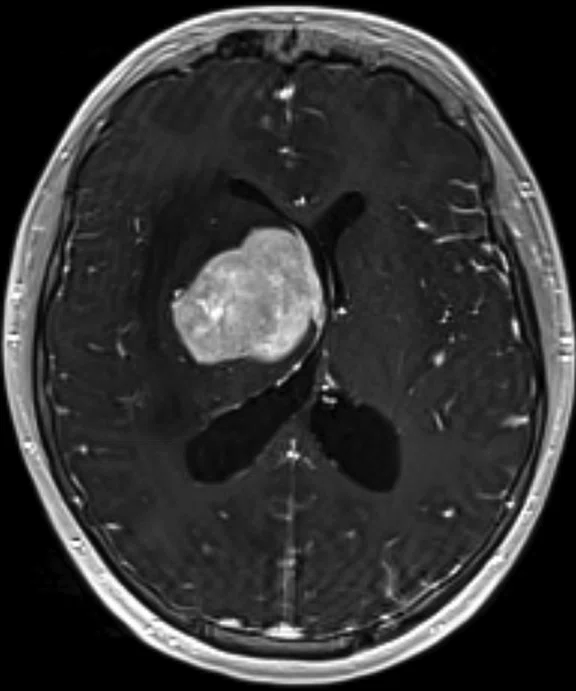

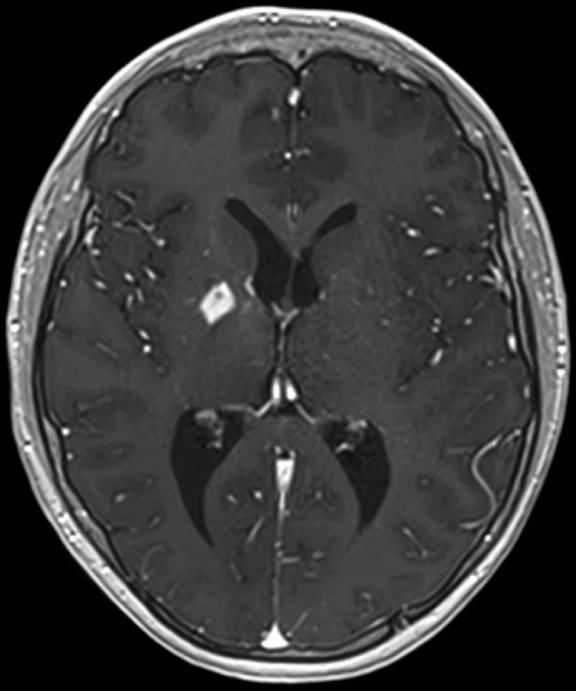

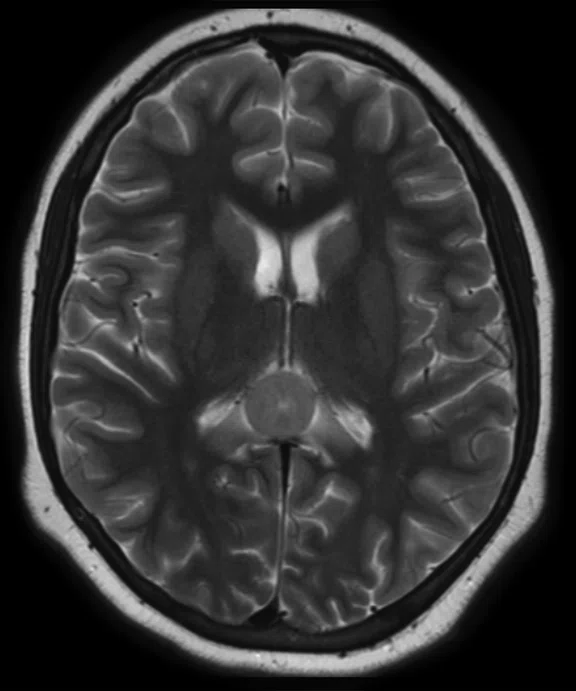

A

Figure 8.

Case 5. After two cycles of chemotherapy, MR imaging depicted an increase in brain lesion size. (A-D) MR images acquired on PET/MR.

B

Figure 8.

Case 5. After two cycles of chemotherapy, MR imaging depicted an increase in brain lesion size. (A-D) MR images acquired on PET/MR.

C

Figure 8.

Case 5. After two cycles of chemotherapy, MR imaging depicted an increase in brain lesion size. (A-D) MR images acquired on PET/MR.

D

Figure 8.

Case 5. After two cycles of chemotherapy, MR imaging depicted an increase in brain lesion size. (A-D) MR images acquired on PET/MR.

A

Figure 10.

Case 6. Seven years post transplant (liver, pancreas and small bowel), patient complained of abdominal pain with fever and vomiting. Using PET/MR, looked for foci of infection/ inflammation/rejection for biopsy. (A) PET MIP; (B, C) PET; (D, E) MR; and (F, G) fused PET/MR.

B

Figure 10.

Case 6. Seven years post transplant (liver, pancreas and small bowel), patient complained of abdominal pain with fever and vomiting. Using PET/MR, looked for foci of infection/ inflammation/rejection for biopsy. (A) PET MIP; (B, C) PET; (D, E) MR; and (F, G) fused PET/MR.

C

Figure 10.

Case 6. Seven years post transplant (liver, pancreas and small bowel), patient complained of abdominal pain with fever and vomiting. Using PET/MR, looked for foci of infection/ inflammation/rejection for biopsy. (A) PET MIP; (B, C) PET; (D, E) MR; and (F, G) fused PET/MR.

D

Figure 10.

Case 6. Seven years post transplant (liver, pancreas and small bowel), patient complained of abdominal pain with fever and vomiting. Using PET/MR, looked for foci of infection/ inflammation/rejection for biopsy. (A) PET MIP; (B, C) PET; (D, E) MR; and (F, G) fused PET/MR.

E

Figure 10.

Case 6. Seven years post transplant (liver, pancreas and small bowel), patient complained of abdominal pain with fever and vomiting. Using PET/MR, looked for foci of infection/ inflammation/rejection for biopsy. (A) PET MIP; (B, C) PET; (D, E) MR; and (F, G) fused PET/MR.

F

Figure 10.

Case 6. Seven years post transplant (liver, pancreas and small bowel), patient complained of abdominal pain with fever and vomiting. Using PET/MR, looked for foci of infection/ inflammation/rejection for biopsy. (A) PET MIP; (B, C) PET; (D, E) MR; and (F, G) fused PET/MR.

G

Figure 10.

Case 6. Seven years post transplant (liver, pancreas and small bowel), patient complained of abdominal pain with fever and vomiting. Using PET/MR, looked for foci of infection/ inflammation/rejection for biopsy. (A) PET MIP; (B, C) PET; (D, E) MR; and (F, G) fused PET/MR.

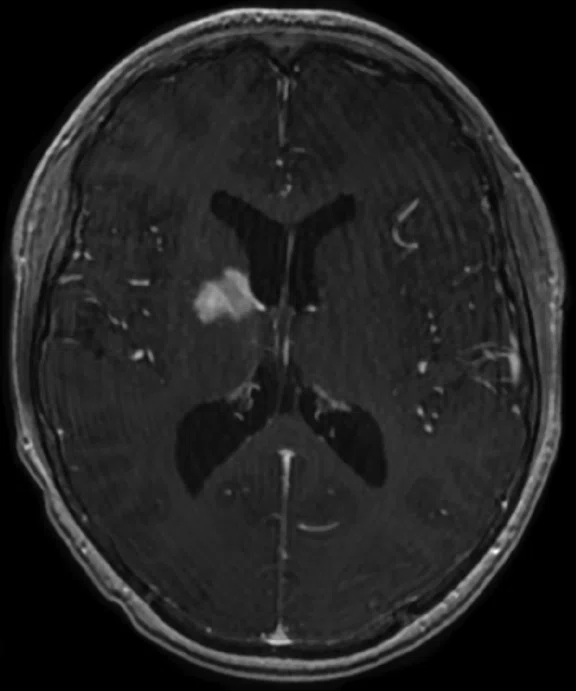

A

Figure 9.

Case 5. Discordant findings between PET and MR in posttreatment PET/MR exam. (A, B) PET; (C, D) MR; and (E, F) fused PET/MR.

B

Figure 9.

Case 5. Discordant findings between PET and MR in posttreatment PET/MR exam. (A, B) PET; (C, D) MR; and (E, F) fused PET/MR.

C

Figure 9.

Case 5. Discordant findings between PET and MR in posttreatment PET/MR exam. (A, B) PET; (C, D) MR; and (E, F) fused PET/MR.

D

Figure 9.

Case 5. Discordant findings between PET and MR in posttreatment PET/MR exam. (A, B) PET; (C, D) MR; and (E, F) fused PET/MR.

E

Figure 9.

Case 5. Discordant findings between PET and MR in posttreatment PET/MR exam. (A, B) PET; (C, D) MR; and (E, F) fused PET/MR.

F

Figure 9.

Case 5. Discordant findings between PET and MR in posttreatment PET/MR exam. (A, B) PET; (C, D) MR; and (E, F) fused PET/MR.

1. Schäfer JF, Gatidis S, Schmidt H, et al. Simultaneous wholebody PET/MR imaging in comparison to PET/CT in pediatric oncology: initial results. Radiology. 2014 Oct;273(1):220-31.

1. Schäfer JF, Gatidis S, Schmidt H, et al. Simultaneous wholebody PET/MR imaging in comparison to PET/CT in pediatric oncology: initial results. Radiology. 2014 Oct;273(1):220-31.

2. Kwon HW, Becker AK, Goo JM, Cheon GJ. FDG Whole-Body PET/MRI in Oncology: a Systematic Review. Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017 Mar;51(1): 22–31

3. Catalano OA, Rosen BR, Sahani DV, et al. Clinical impact of PET/MR imaging in patients with cancer undergoing same-day PET/CT: initial experience in 134 patients—a hypothesis-generating exploratory study. Radiology. 2013, Dec;269(3):857–69.

A

Figure 10.

Case 6. Seven years post transplant (liver, pancreas and small bowel), patient complained of abdominal pain with fever and vomiting. Using PET/MR, looked for foci of infection/ inflammation/rejection for biopsy. (A) PET MIP; (B, C) PET; (D, E) MR; and (F, G) fused PET/MR.

B

Figure 10.

Case 6. Seven years post transplant (liver, pancreas and small bowel), patient complained of abdominal pain with fever and vomiting. Using PET/MR, looked for foci of infection/ inflammation/rejection for biopsy. (A) PET MIP; (B, C) PET; (D, E) MR; and (F, G) fused PET/MR.

C

Figure 10.

Case 6. Seven years post transplant (liver, pancreas and small bowel), patient complained of abdominal pain with fever and vomiting. Using PET/MR, looked for foci of infection/ inflammation/rejection for biopsy. (A) PET MIP; (B, C) PET; (D, E) MR; and (F, G) fused PET/MR.

D

Figure 10.

Case 6. Seven years post transplant (liver, pancreas and small bowel), patient complained of abdominal pain with fever and vomiting. Using PET/MR, looked for foci of infection/ inflammation/rejection for biopsy. (A) PET MIP; (B, C) PET; (D, E) MR; and (F, G) fused PET/MR.

E

Figure 10.

Case 6. Seven years post transplant (liver, pancreas and small bowel), patient complained of abdominal pain with fever and vomiting. Using PET/MR, looked for foci of infection/ inflammation/rejection for biopsy. (A) PET MIP; (B, C) PET; (D, E) MR; and (F, G) fused PET/MR.

F

Figure 10.

Case 6. Seven years post transplant (liver, pancreas and small bowel), patient complained of abdominal pain with fever and vomiting. Using PET/MR, looked for foci of infection/ inflammation/rejection for biopsy. (A) PET MIP; (B, C) PET; (D, E) MR; and (F, G) fused PET/MR.

G

Figure 10.

Case 6. Seven years post transplant (liver, pancreas and small bowel), patient complained of abdominal pain with fever and vomiting. Using PET/MR, looked for foci of infection/ inflammation/rejection for biopsy. (A) PET MIP; (B, C) PET; (D, E) MR; and (F, G) fused PET/MR.

A

Figure #.

Figure Copy.

B

Figure #.

Figure Copy.

C

Figure #.

Figure Copy.

D

Figure #.

Figure Copy.

A

Figure 4.

Case 3. Adjuvant therapy shrunk the primary tumor and two hot spots leading to negative surgical margins. (A, C, E) PET/MR exam prior to treatment and (B, D, F) PET/MR two- and one-half months after start of treatment.

B

Figure 4.

Case 3. Adjuvant therapy shrunk the primary tumor and two hot spots leading to negative surgical margins. (A, C, E) PET/MR exam prior to treatment and (B, D, F) PET/MR two- and one-half months after start of treatment.

C

Figure 4.

Case 3. Adjuvant therapy shrunk the primary tumor and two hot spots leading to negative surgical margins. (A, C, E) PET/MR exam prior to treatment and (B, D, F) PET/MR two- and one-half months after start of treatment.

D

Figure 4.

Case 3. Adjuvant therapy shrunk the primary tumor and two hot spots leading to negative surgical margins. (A, C, E) PET/MR exam prior to treatment and (B, D, F) PET/MR two- and one-half months after start of treatment.

E

Figure 4.

Case 3. Adjuvant therapy shrunk the primary tumor and two hot spots leading to negative surgical margins. (A, C, E) PET/MR exam prior to treatment and (B, D, F) PET/MR two- and one-half months after start of treatment.

F

Figure 4.

Case 3. Adjuvant therapy shrunk the primary tumor and two hot spots leading to negative surgical margins. (A, C, E) PET/MR exam prior to treatment and (B, D, F) PET/MR two- and one-half months after start of treatment.

result

PREVIOUS

${prev-page}

NEXT

${next-page}

Subscribe Now

Manage Subscription

FOLLOW US

Contact Us • Cookie Preferences • Privacy Policy • California Privacy PolicyDo Not Sell or Share My Personal Information • Terms & Conditions • Security

© 2024 GE HealthCare. GE is a trademark of General Electric Company. Used under trademark license.

SPOTLIGHT

Thirty-minute PET/MR exam for pediatric cancer patients

Thirty-minute PET/MR exam for pediatric cancer patients

By Jing Qi, MD, Assistant Professor, and Nghia (Jack) Vo, MD, Chief of Pediatric Radiology, Medical College of Wisconsin

Clinicians at the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin have developed a 30-minute PET/MR exam for evaluating pediatric cancer patients. After comparing the results of PET/MR to PET/CT in many patients across different disease types and conditions, the facility has successfully converted all PET/CT studies to PET/MR. In several instances, PET and MR are discordant, helping improve the diagnosis.

Clinicians at the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin have developed a 30-minute PET/MR exam for evaluating pediatric cancer patients. After comparing the results of PET/MR to PET/CT in many patients across different disease types and conditions, the facility has successfully converted all PET/CT studies to PET/MR. In several instances, PET and MR are discordant, helping improve the diagnosis.

SPOTLIGHT

Thirty-minute PET/MR exam for pediatric cancer patients

Thirty-minute PET/MR exam for pediatric cancer patients

By Jing Qi, MD, Assistant Professor, and Nghia (Jack) Vo, MD, Chief of Pediatric Radiology, Medical College of Wisconsin

Clinicians at the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin have developed a 30-minute PET/MR exam for evaluating pediatric cancer patients. After comparing the results of PET/MR to PET/CT in many patients across different disease types and conditions, the facility has successfully converted all PET/CT studies to PET/MR. In several instances, PET and MR are discordant, helping improve the diagnosis.

Clinicians at the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin have developed a 30-minute PET/MR exam for evaluating pediatric cancer patients. After comparing the results of PET/MR to PET/CT in many patients across different disease types and conditions, the facility has successfully converted all PET/CT studies to PET/MR. In several instances, PET and MR are discordant, helping improve the diagnosis.

The Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW) is an academic partner of the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, a top-ranked pediatric hospital and one of the nation’s busiest. While PET/CT had been utilized for the diagnosis and staging of cancer patients, our facility acquired a SIGNA™ PET/MR in late 2017 and scanned our first patients in February 2018. The PET/MR is clinically utilized for 75% of our oncology cases, primarily sarcoma and lymphoma, and 25% for brain cases, including seizures and tumors.

A 2014 study published in Radiology of 20 whole-body PET/CT and PET/MR exams in 18 pediatric patients reported that PET/MR demonstrated equivalent lesion detection rates in pediatric oncology cases compared to PET/CT. The study indicated that MR had a higher sensitivity than PET or PET/CT for solid organs and bone lesions and in several cases provided additional diagnostic information in areas of soft tissue.1 Further, the lack of ionizing radiation exposure from CT makes PET/MR an attractive alternative, as many children will receive multiple imaging exams during their course of treatment.1

Additionally, a review article on FDG PET/MR imaging for malignancies noted that the additional morphologic and functional information provided by MR may help further characterize FDG uptake in a suspicious lesion.2 Another study reported that additional findings from PET/MR impacted patient clinical management in nearly 18% of cases.3

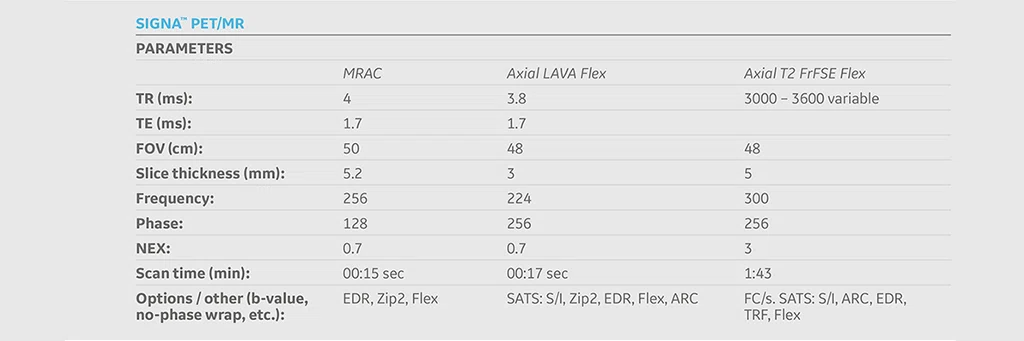

The disadvantage of PET/MR compared to PET/CT is the longer scan times for MR versus CT. We addressed this issue by taking PET as the time-limiting factor and tailoring our MR sequences to fit into the PET acquisition times. Based on three-minute per bed positions, we acquire a 15-second MRAC to generate an AC Map, a 40-second Axial T1 LAVA Flex sequence for anatomic registration and then a two-minute Axial T2 frFSE Flex for pathology survey. The T2 frFSE Flex generates both FatSat and non-FatSat images, while the T1 LAVA is acquired in 3D so we can reformat the data into Coronal and Sagittal views for image registration with PET.

Further, the ability to provide concurrent MR with PET in the same setting under one sedation is best for the pediatric patient and their parents. The oncologists are also pleased with the information we are able to provide in a three-minute PET/MR per bed exam, as demonstrated in the following patient cases. We are continuing to evaluate the efficacy of this short PET/MR exam in the long-term management of lymphoma and sarcoma, as well as investigate the use of PET/MR in pheochromocytoma and possible medulloblastoma patients.

With the implementation of PET/MR, we have successfully converted PET/CT imaging studies for our pediatric cancer patients to PET/MR.

Case 1

A 21-year-old Hodgkin’s lymphoma patient originally staged with PET/CT. Patient was scanned using PET/MR on the second day of clinical service. Patient was scanned with seven bed positions, three minutes each bed position, for a total scan time of 21 minutes.

Results: Complete response with uptake equivalent to the blood pool. Tumor is dark on T2-weighted sequence, suggesting fibrotic changes or scar tissue. Patient remained PET negative at completion of the chemotherapy.

Case 2

A 16-year-old female with desmoplastic small round cell tumor was the first patient to undergo only PET/MR (no PET/CT). Patient had widespread disease throughout the abdomen, including a pelvic lesion and soft tissue mass coating the diaphragm. The patient had debulking surgery and was referred for restaging. Unfortunately, due to her size (200 lbs., 5 feet 4 inches and BMI 32) the bellow belt for breathing/gating kept catching on the bore and the scan would abort. We eventually decided to not use respiratory gating for the study. PET/MR images were acquired two hours after injection, yet despite the low photon count we were able to acquire good diagnostic-quality images.

Results: A suspicious residual, hyperdense lesion in the pelvis seen on CT was well characterized on MR, low intensity on both T1 and T2-weighted sequences and without FDG uptake, most consistent with a complex fluid collection (Figure 2).

The diaphragm lesion is well seen on the T2 FatSat image and the Sagittal reformat (Figure 2C, 2D) even with the free-breathing sequence and it correlates with abnormally increased FDG uptake. Findings are consistent with residual disease.

Figure 2.

Case 2. A 16-year-old patient with residual disease over the pleural surface of the diaphragm (red arrows). Despite imaging the patient two hours after FDG, good diagnostic quality images were still acquired on PET. The hyperdense residual lesion is well characterized by MR. (A, B) PET with (C, D) corresponding T2 FatSat MR slices.

Case 3

A newly diagnosed 13-year-old patient with Ewing’s sarcoma was referred to PET/MR to confirm initial diagnosis on a dedicated MR system. In this case, the quality of the T2 frFSE Flex sequence captured on the PET/MR was similar to the dedicated MR. There are two small foci next to the spine that correspond with lesions in the deep fascia of the spinal muscle and the other in a paraaortic lymph node. In retrospect, those can be seen on the diagnostic MR performed five days prior (Figure 3C, 3D).

Results: Patient had a tumor in the left spinal muscle with high-grade FDG uptake at time of staging. Adjuvant therapy shrunk the primary tumor and two hot spots (Figure 4), leading to negative surgical margins.

Figure 3.

Case 3. A 13-year-old female with Ewing’s sarcoma. (A) PET image from PET/MR exam; (B) T2 frFSE Flex FatSat from PET/MR exam; and initial diagnostic MR exam (C) T2 frFSE Flex FatSat and (D) T1 contrast enhanced. The quality of the (B) T2 frFSE Flex FatSat on PET/MR is the same quality as the (C) T2 frFSE Flex FatSat on the dedicated MR.

Case 4

A 16-year-old patient with large B cell lymphoma who relapsed with lesions in the brain and underwent salvage chemotherapy. Monthly dedicated MR imaging demonstrated a continual decrease of the lesions in the first two months of therapy that lessened near the end of the treatment. Stem cell transplant was planned; however, the patient prognosis is better if they have complete remission. We proposed PET/MR to help determine if the lesions were scar tissue or viable tumors, and whether the patient was in complete remission. The PET study was acquired concurrently with a dedicated MR study.

Results: Uptake in the right basal ganglia corresponds with enhancement on the MR, suggestive of a residual lesion. Patient underwent another round of chemotherapy prior to stem cell transplant.

Case 5

A 12-year-old with undifferentiated sarcoma, widespread disease in the chest, abdomen, pelvis and the thigh muscles. There appears to be foci in the corpus callosum.

Results: There are discordant findings between MR and PET in the posttreatment imaging: there is an increase in the lesion size on the MR image and a decrease in activity in the PET image. There appears to be a progression of disease and this patient will be followed using PET/MR.

Case 6

A 9-year-old patient who underwent a liver, pancreas and small bowel transplant at age 2. Patient has abdominal pain, fever and vomiting. Initially, a white blood cell scan using nuclear medicine was ordered; however, we recommended PET/MR due to its higher spatial and contrast resolution. We utilized PET/MR to look for foci of infection, inflammation or organ rejection, as well as provide sites/targets for biopsy.

Results: There are two foci in the abdomen with FDG uptake: one in the right quadrant that correlates with the small bowel and the other next to the surgical anastomosis in distal small bowel. With the PET/MR exam, we were able to provide two areas for biopsy.